Artificial intelligence is changing the face of waste education. City staff and facility operators are looking beyond just paper mailers and public service announcements to cameras, screens and text prompts. The technology is designed to meet users at the bins and help them navigate the complexities of local recycling rules.

AI has been used to identify items and trigger physical separation within MRFs for years, and more recently it’s even been implemented to track contamination levels at the point of collection when haulers integrate camera systems into their trucks. But neither of these use cases go as far upstream as trying to help consumers make the right decision about where to put their refuse, recyclables or organics.

“This was really an effort to help people better understand small nuances, and it also gave us new insights about common questions and gaps in knowledge,” said Pamela Perez, the marketing manager for LA Sanitation & Environment, which recently introduced Professor Green, an AI tool for organics recycling education.

Proponents of these AI feedback systems hope they can cut down on contamination and increase capture rates, but the technology is still evolving.

Whether the tools are chatbots or item-identifying cameras, operators have to tinker with the software over time and hone its ability to offer users the right responses. Experts say that accurate item identification — particularly at the curb, where trash and recycling come in an almost infinite number of forms — could be a challenge for some iterations of this consumer-facing AI. Another hurdle will be convincing consumers to use it.

Send a text or take a photo

Contamination rates remain stubbornly high, as recycling rates are also stagnant in many parts of the U.S.

In New York City, for example, non-recyclable contaminants in the metal, plastic and glass waste stream have gone from nearly 34 pounds to almost 49 pounds per household between 2017 and 2023. The Recycling Partnership estimated in 2020 that the inbound material contamination rate was 17%.

Waste and recycling professionals hoping to improve these statistics are looking to AI as enabling coaching for residents and visitors on the spot.

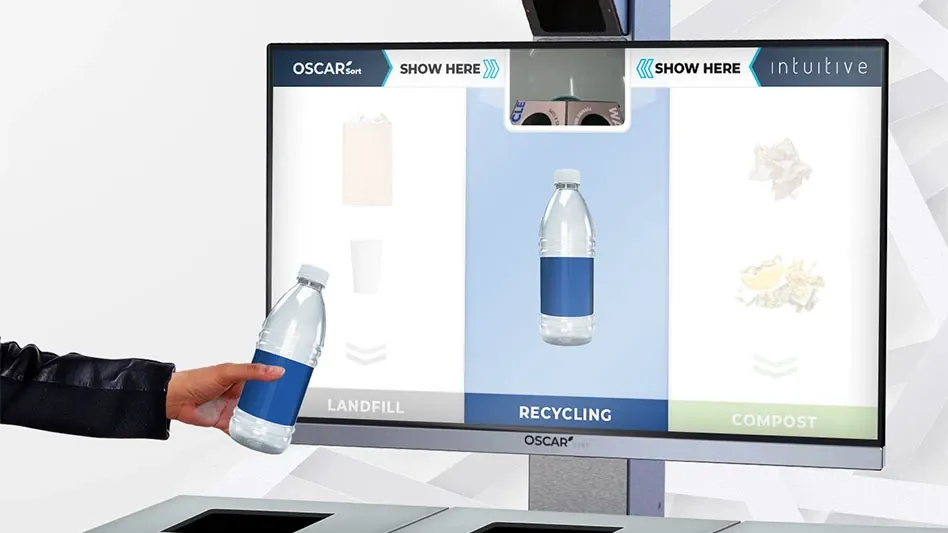

Some public-facing AI sorting systems identify items the same way MRF technologies do. Oscar Sort, a platform offered by Intuitive AI, uses a camera to see what a user is holding. A follow-up message on a mounted screen shows which bin to drop it in — trash, recycling, compost, or even (as one client requested) a chopstick-only receptacle for a recycling service to turn into wooden furniture. The software can also offer multi-part instructions, like directing a coffee cup to the trash bin and a cardboard sleeve to the recycling bin.

In the U.S., facilities such as the San Francisco Ferry Building and Seattle-Tacoma International Airport are in the early stages of using Oscar on site. The company says over 25 airports and 50 universities asked to become customers in the last year.

Each Oscar installation costs $10,000 to $15,000, after which yearly services and data fees cost $5,500 to $6,500, said Brian Sano, head of strategy at Intuitive AI. In 2024, the company launched an ad-based offering — brands can pay to advertise on the embedded screens, generating potentially enough revenue for the facility to cover annual maintenance costs and then some.

Consumer-facing sorting AI can also take in what the public offers via text, which is how the city of Los Angeles opted for its technology to operate.

Professor Green, the AI educator built for the city by software company Hello Lamp Post, works like a chatbot. Users in one of four pilot neighborhoods — Porter Ranch, Northridge, South LA and Watts — scan a QR code or go to the city website to text Professor Green. The system replies to tell users if their item can go in a city-provided green bin, or their trash or recycling bins instead. The chatbot understands and replies to English, Spanish, Korean, Tagalog, Ethiopian and Armenian — languages selected to best serve populations in the pilot area.

Ideally, Professor Green clears up local confusion about composting rules. The City of Los Angeles has a lot of residents who move in to the municipality and might not be familiar with local guidelines, Perez said, or need help parsing the rules from those of nearby areas. For example, some of the other municipalities in Los Angeles County asks that residents line their bins with compostable bags, but the city of Los Angeles only accepts paper-product liners.

Too few trash photos

Both Intuitive AI and LA Sanitation staff dip into the data to make sure that their programs are identifying items correctly.

Intuitive AI does this for Oscar customers by comparing the instructions Oscar offered to the recordings of what the user was holding, every day, along with four waste audits a year for most customers.

LA Sanitation staff also comb through Professor Green requests every day. They spend at most an hour on the inquiries, which is often more than enough time to spot any issues. For example, staff taught the AI to respond to questions about tamale waste, but soon realized it didn’t know corn husks were part of the food. Perez said the team has since instructed Professor Green to associate the two.

Text-based sorting inquiries will likely give users more accurate instructions than camera-based technology, said Sharon Hsiao, an assistant professor of computer science and engineering at Santa Clara University.

That’s because having people tell the AI what they’re trying to dispose of gets around the issue of having to train the software to recognize what trash looks like. Written prompts can still run a wide range. As Perez pointed out, her office had a long list of terms for “pet waste” that Professor Green needed to recognize. But visual identification has even more variability.

“Cigarette butts or COVID masks — those are very distinct,” Hsiao said. “But if you crumple up paper, it won’t always be the same shape.”

There are also few photos of trash that are freely available for AI models to learn from.

Hsiao and her colleagues tried to compile a database of these publicly accessible training images when building an AI waste sorter that relies on a smartphone camera. Not only were there too few images to train the software, but the computational power that would be needed for the AI to recognize any possible item goes beyond anything a smart phone can handle, Hsiao said.

An AI system focused on waste requires a small computer and is more likely to be accurate if developers can train the software to recognize a limited array of items, Hsiao said. Places that restrict the kinds of materials allowed inside, like entertainment venues or airports, could be a natural fit.

Lower barriers are better

Experts expect technology to play an increasing role as local governments and facility operators look for ways to evolve their recycling education. But figuring out what will resonate with the public is an ongoing process.

AI-enabled camera systems might be easier for users, despite being harder to teach. In surveys, Hsiao and her team found that people are likely to think of texting or responding to voice prompts as more work than waiting for a camera to register what it’s seeing. And all of these options were considered significantly more time-consuming than the status quo —the split-second decision of throwing items into whichever bin it seems to belong.

“All the people that we surveyed wanted to be able to use their phone to scan items to tell them which bin it's supposed to be in,” Hsiao said. “In reality, they actually don't do it.”

To convince people to take the time and use the AI identification they claim to want, Hsiao and her colleagues are working on a sorting system that also tells users about the benefits of their actions. Her team is experimenting with feedback about money or greenhouse gas emissions saved via correct sorting.

For now, the simpler text-based Professor Green option appears to be resonating. Los Angelenos have had over 4,000 conversations with the AI since its debut in March. Use has been particularly high in South LA, a low-income neighborhood where the majority of households speak Spanish at home.

LA Sanitation is now looking at expanding Professor Green to other neighborhoods in the future. But to know for certain whether the AI system is meaningfully changing contamination rates or diverting more material from landfills, Perez and her team would have to see the results of a more old-fashioned tool: A waste audit.

This story first appeared in the Waste Dive: Recycling newsletter. Sign up for the weekly emails here.