During a 1991 interview on a Minnesota Public Radio program, a caller brought up earth-friendly claims on packaging and called the labels unclear. “I'm confused half the time,” he said. “I don't know what they're trying to say.”

Minnesota Attorney General Hubert “Skip” Humphrey, the show’s guest, agreed.

“I was just in the store the other evening, and I went down one of those aisles, and sure thing there were some claims just as you were indicating. One of the spray cans had said that it was environmentally safe. Whatever that meant…” he replied.

This was a decade after scientists began raising concerns about the effects of chemicals from aerosol sprays and refrigerators on the ozone layer, and a few years after the Montreal Protocol treaty was signed in an effort to phase them out, but marketers still faced little scrutiny about their ozone-friendly claims.

That changed on July 28, 1992, when the Federal Trade Commission — responding to pressure from a group of attorneys general led by Humphrey, and from manufacturers looking for guidance — released the Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims.

These guidelines, quickly nicknamed the Green Guides, sought to provide clear guidance on the types of environmental marketing claims companies could make about their products and packaging. They have since helped make the term “greenwashing” a household term and influenced multiple shifts over the years.

Although the Green Guides are not separately enforceable, the agency can use them to bring cases using the Federal Trade Commission Act, which outlaws unfair methods of competition and acts or practices that affect commerce.

After updating the guides again in 1996, 1998 and 2012, the FTC is currently considering what could be one of its most consequential Green Guides updates yet.

With public debate growing over the effectiveness of recycling, and over how much influence the Green Guides can hold as more states take legislative approaches to regulate environmental marketing, this update is set to potentially mark a sea change in the FTC’s approach.

Green Guides déjà vu

The results of a survey by J. Walter Thompson Co., published in Advertising Age in 1990, found that 96% of consumers felt they needed more information to understand environmental marketing claims. So in publishing the Green Guides, the FTC sought to steer companies toward structuring claims in a way that consumers could understand — for example, whether a package is recyclable and how to dispose of it — while also making it easy for marketers to meet the guidelines with language that could be substantiated.

Fast forward more than 30 years and modern consumers have grown up with recycling systems, but they have a new, and perhaps far more difficult concern to address: quickly growing distrust.

Suzanne Shelton, president and CEO of market research firm Shelton Group, said that years of marketing focused on recyclability allowed packaged goods companies to quell consumers’ concerns about consumption. In her view, the message was “buy stuff, and don't feel bad about it, because you're just gonna chuck it into the blue bin, and it's gonna go to a magical place called ‘away,’ and it will become something else.”

But that has changed. Recent research from Shelton’s firm, which surveyed 6,500 people, suggests that nearly a third of Americans are not confident that what they toss in the recycling bin is actually recycled. Four years ago, that was only 14%.

This current moment also has other notable parallels to the early 1990s.

Then, many state governments were considering or enacting regulations meant to govern environmental marketing claims. Today, recent laws passed by California and Oregon are forcing marketers to change how they communicate recyclability, such as by removing the chasing arrows around resin identification codes in favor of clear and accurate recycling directions.

Back then, technologies related to packaging were evolving quickly with a big focus on biodegradability. Now, the conversations are about chemical recycling of plastics and scaling plant-based and compostable materials.

The macro-sustainability issues then were around ozone depletion and landfill space. Today those issues are around carbon emissions and material circularity.

Another key parallel is that in the early ‘90s, consumers were eager to integrate sustainability into purchasing decisions but were confused or distrustful about whether product packaging that they put into the recycling stream was actually recycled.

“There was really a kind of ‘wild west’ environment in which companies were recognizing that there was a competitive advantage in being good for the environment,” said Doug Blanke, who was assistant attorney general and director of the consumer protection division of the Minnesota Attorney General’s office during Humphrey’s tenure.

In response, Blanke said some manufacturers “reformulated their products” but others “just reformulated their advertising.” He pointed to fast food companies as a prime example, some of which were putting food in polystyrene foam containers that bore recycling symbols.

“When we looked into it, it turned out it was technically possible to recycle Styrofoam, but the nearest facility that did that was in Chicago, 400 miles from Minnesota. You weren't going to mail your McDonald's container to Chicago for recycling,” said Blanke.

After the FTC issued the Green Guides, Blanke went to focus on consumer protections related to the tobacco industry, but he believes the Green Guides were effective and worked as they were intended.

Marketers, manufacturers, consumer and environmental groups all got what they wanted: clear guidelines in language that all stakeholders could understand. And the legal cases that the AG task force brought and won before and after the guides were issued — including one against a maker of diapers that it claimed were biodegradable — sent an effective message to other companies that they could be opening themselves up to legal scrutiny.

“You don't want to be the poster child for being environmentally irresponsible,” said Blanke. “I mean, biodegradable diapers. Come on.”

Blanke does not, however, think the FTC would have developed the Green Guides if not for the pressure the AG task force enacted. Nor does he think as many state AGs today could come together as seamlessly because it was a less partisan environment.

Not all stakeholders were bullish on the guides after they came out. Writing in Marketing News (a publication of the American Marketing Association), Bentham Paulos, an environmental researcher, and Andrew Stoeckle, a senior analyst for Abt Associates, said in 1993 it was “uncertain that [the Guides] are having the effect that marketers desired.”

They described two complaints from marketers: that the guidelines were voluntary in theory but not practice, amounting to a Catch-22 wherein the FTC was saying “we will not force you to do something if you volunteer to comply with our suggestions.” Secondly, they said the Green Guides had not and could not address the looming problem of state laws aimed at regulating environmental marketing claims.

The hope, however, was that any states seeking to enact new laws would use the Green Guides to direct those regulations, thereby reducing the likelihood that marketers would need to change course in their environmental marketing strategy.

The guides’ evolution

In the two years following the release of the inaugural guides in 1992, a group of researchers from the University of Illinois and the University of Utah audited their early impact by examining the labels of brands sold in supermarket product categories.

Over the research period, the researchers found that brands had made notable changes in line with the FTC’s guidelines. Environmental claims generally became more specific and meaningful over the audit period. Claims referencing ozone decreased, likely because the Green Guides instructed marketers to substantiate the claims, but general environmental commitment claims nearly tripled.

Package recyclability claims increased, but not in a manner that necessarily helped alleviate consumer confusion because — misaligned with the Green Guides — they lacked specificity and most were vague, such as “please recycle.” Yet, the guides instructed marketers to provide specific instructions on where or how to recycle packaging or products unless recycling facilities were available to “a substantial majority of consumers or communities.”

During the first update, in 1996, language was added to require marketers to substantiate claims such as “environmentally preferable,” and the FTC tried to clarify directions on how to use the chasing arrows symbol. It advised marketers to specify whether the symbol was being used to indicate recycled content or recyclability. Plus, it instructed marketers to indicate where to recycle items and how much recycled content they contained, if any.

With environmental marketing growing briskly, along with consumer interest in sustainable products, the FTC quickly made a second set of revisions in 1998.

These included that recyclability claims could include “the reuse, reconditioning, and remanufacturing of products or parts in another product” and that recycled content claims should be made for “only those products or packages that were reused in the form of ‘raw materials’ in the manufacture or assembly of a ‘new’ package or product.” With multi-channel commerce growing, the agency also made clear that service marketers and marketing done via the internet and email were also expected to follow the guides.

The agency did not issue another update until 2012. It started the process in 2007 with workshops and was expected to issue the updates in 2010, but efforts slowed during the transition between presidential administrations starting in 2008.

In addition to new sections on the use of carbon offsets, green certifications and seals, and renewable energy and renewable materials claims, the 2012 Green Guides included several other revisions related to packaging, such as compostability claims. In addition to making clear whether packaging or products would become usable compost “in a safe and timely manner” in an industrial compost setting or a home garden setting, the updates clarified that ‘‘timely” means ‘‘in approximately the same time as the materials with which it is composted.’’

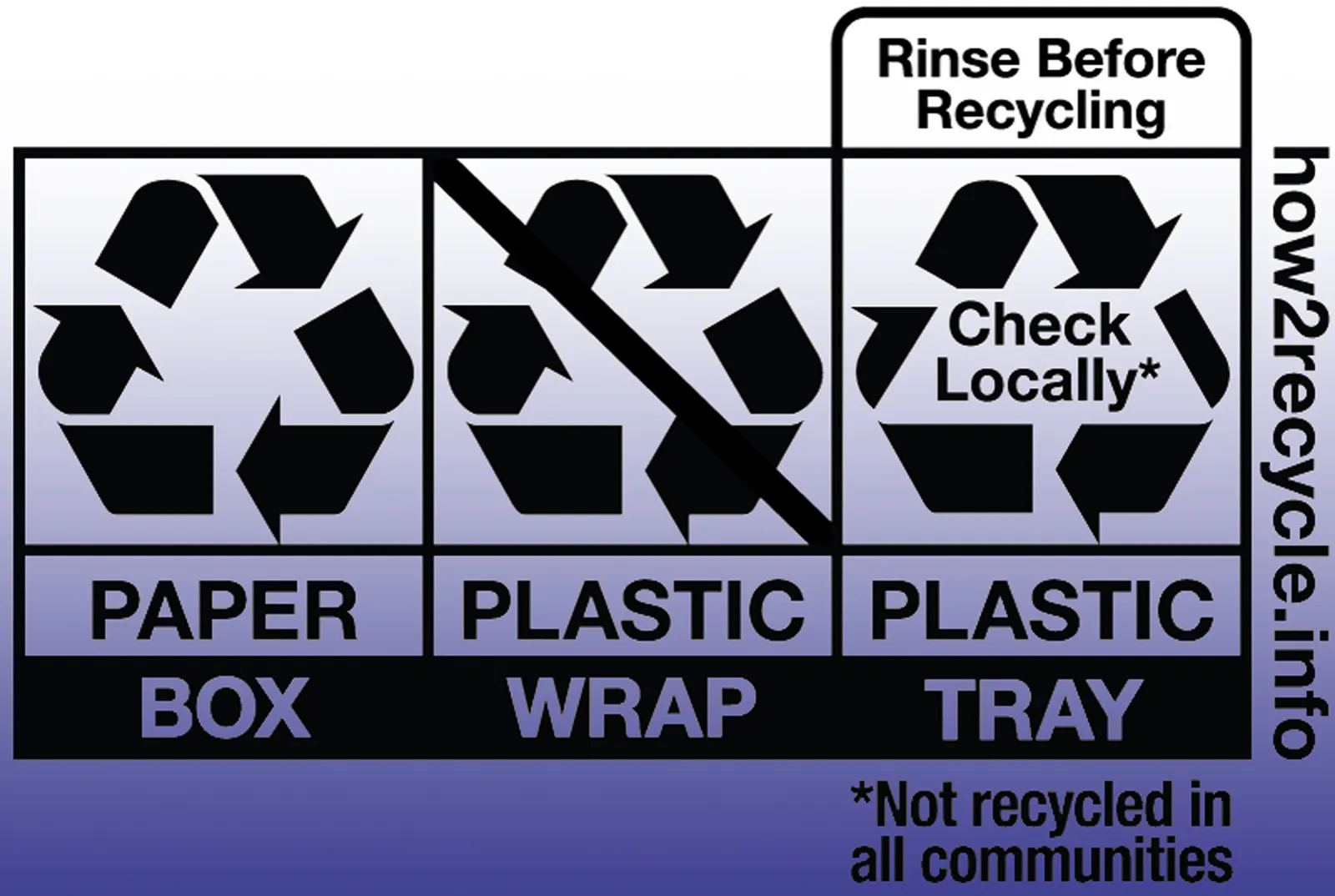

While earlier iterations advised marketers to qualify recyclable claims when facilities are not available to a ‘‘substantial majority’’ of consumers or communities, the 2012 update clarified that meant at least 60%, and that “the lower the levels of access to appropriate facilities, the more strongly the marketer should emphasize the limited availability of recycling for the product.” This change soon led to voluntary brand-backed systems such as the How2Recycle label, which have become a point of discussion in the latest update process.

In comments submitted to the FTC regarding the next round of updates, industry and advocacy groups have shared their differing views on updating the guides to reduce problems such as contamination in the recycling stream. In some cases recyclers want to see more clear language on certain products, while the companies behind those products want a more nuanced approach to recyclability claims for newer materials.

While the groups disagree on some issues, many agree that the current guidelines are not adequately informing consumers or preventing misleading claims.

Past and future enforcement battles

While the guides have prompted many broader debates, the FTC’s actual level of enforcement has ebbed and flowed.

The agency joined with seven states, suing Mobil for selling Hefty trash bags as “degradable” when exposed to light, air and water. Mobil agreed to stop the advertising campaign and it paid $150,000 in settlement claims in 1991, prior to the enactment of the Green Guides. It was the first suit to result in consent orders against a company charged with making false environmental claims, but not the last.

The agency spent nearly a decade on cases related to a plastic additive that a manufacturer claimed made plastic biodegradable. In 2013 it announced six enforcement actions, including one that imposes a $450,000 civil penalty.

But the FTC is not the only organization that uses the Green Guides to keep marketers in compliance. The National Advertising Division, a system of independent industry self-regulation affiliated with BBB National Programs, also employs them in its efforts.

“It's the advertising industry's effort to self police, to hold itself to standards that are going to protect their brands, not confuse consumers, allow everyone to compete on a level playing field, so that everyone kind of knows the rules and operates in a way that's clear and transparent,” said David Mallen, who spent 15 years as deputy director of NAD before joining private practice. He’s now an advertising and media attorney with Loeb & Loeb.

The NAD recently brought a case against American Beverage, telling the group to modify “certain aspirational claims regarding the use of recycled materials in bottles, as well as claims relating to ABA’s partnerships with non-profit organizations and efforts to achieve sustainability goals together.”

As the FTC develops the next Green Guides update, Shelton said her many clients in the packaging value chain are acutely focused on how and whether chemical recycling will be addressed.

“I think there's a lot of worry that the FTC is going to make some call on this that's going to devastate the industry because that's where things are moving. The hard-to-recycle packaging and the multilayer packaging, all of that is moving towards chemical recycling,” she said.

But, she said that overall, her clients do make sure they follow the FTC’s Green Guides to the letter, especially because the agency continues bringing lawsuits based on egregious violations.

“Our clients tend to treat them as if they're the law,” Shelton said. “In my mind it works like it's supposed to. It's like having a school crossing guard.” A crossing guard is not a police officer, “but the presence of someone who looks authoritative tends to make you toe the line.”

And just as they did back in the early ‘90s, state attorneys general are weighing in about what changes they’d like to see. But given that this latest coalition of AGs is all Democrats that are pushing the FTC to set a high bar on what can be called recyclable, and cautioning against allowances for chemical recycling, partisan politics might start playing an even bigger role.

Mallen says that looking ahead to the next revision of the Green Guides, it’s important to keep in mind that the agency’s goal “isn't really to achieve any particular environmental outcome, it's to make sure that consumers aren't being misled.”

Therefore, transparency is the ultimate goal, even if it means not telling consumers what they want to hear.

“If you tell consumers, ‘you’ve got to take this to the store, or it's not going to be recycled,’ that's maybe not a great result for the folks that are concerned about all the plastics in the landfill,” he said. “But you're at least raising the bar in terms of realistic outcomes and expectations. And maybe that's all advertising can do at the end of the day is just be clear and be transparent.”

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas contributed to this story.

Correction: This article has been updated to correct the name of a nonprofit affiliated with the National Advertising Division.

Interested in more packaging news? Sign up for Packaging Dive’s newsletter today.