The ongoing debate over who should be liable for contamination from PFAS-containing materials continued during a congressional hearing Thursday held by the House Energy & Commerce’s environment subcommittee.

Representatives from water utilities pressed lawmakers to take action in 2026 to protect them from what they see as unfair liability exposure, while environmental group Clean Cape Fear urged further national regulation of PFAS as a hazardous waste in order to prevent more residents from high exposures linked with health concerns like cancer.

For the last few years, the waste industry, along with related industries such as water treatment facilities, have sought an exemption from certain PFAS liability under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, or CERCLA.

Industry groups say they are “passive receivers” of PFAS, meaning they do not generate PFAS, nor have control over PFAS-containing items that enter their facilities. These groups worry they will face lawsuits or high cleanup costs for receiving or handling PFAS-containing items.

But environmental groups have said such exemptions allow bad actors to continue polluting and expose vulnerable communities to further harm.

Thursday’s hearing mirrored themes that were discussed at a separate Senate hearing in November in the Environment and Public Works Committee, where waste companies advocated for passive receiver exemptions.

These multiple year-end hearings show that PFAS regulations are still top of mind for some lawmakers, even as the U.S. EPA earlier this year rolled back parts of its PFAS drinking water standard.

Discussions on PFAS-related liability have also ramped up in the year since the EPA designated two of the PFAS chemicals, PFOS and PFOA, as hazardous substances under CERCLA. At that time, the EPA said it does not intend to pursue municipal landfills or water utilities in its enforcement strategy. But waste and water groups have said it’s not enough to protect them from liability.

The National Waste & Recycling Association sued over the designation, arguing it exposed waste facilities to liability. The EPA said in September that it would defend the decision in court.

Susan Bodine, a partner with Earth & Water Law, said during Thursday’s hearing that CERCLA already provides some exclusions from liability, but aren’t enough to “help most insignificant contributors or inadvertent parties that may face liability for PFAS contamination.”

Water treatment facilities and the waste industry have aligned on their calls for Congress to pass legislation specifically exempting them from such CERCLA liability. Lawmakers have introduced such bills several times in recent years, but so far there has been little movement.

During the hearing, the American Water Works Association called on Congress to pass the Water Systems PFAS Liability Protection Act, which was introduced in February but has not moved forward.

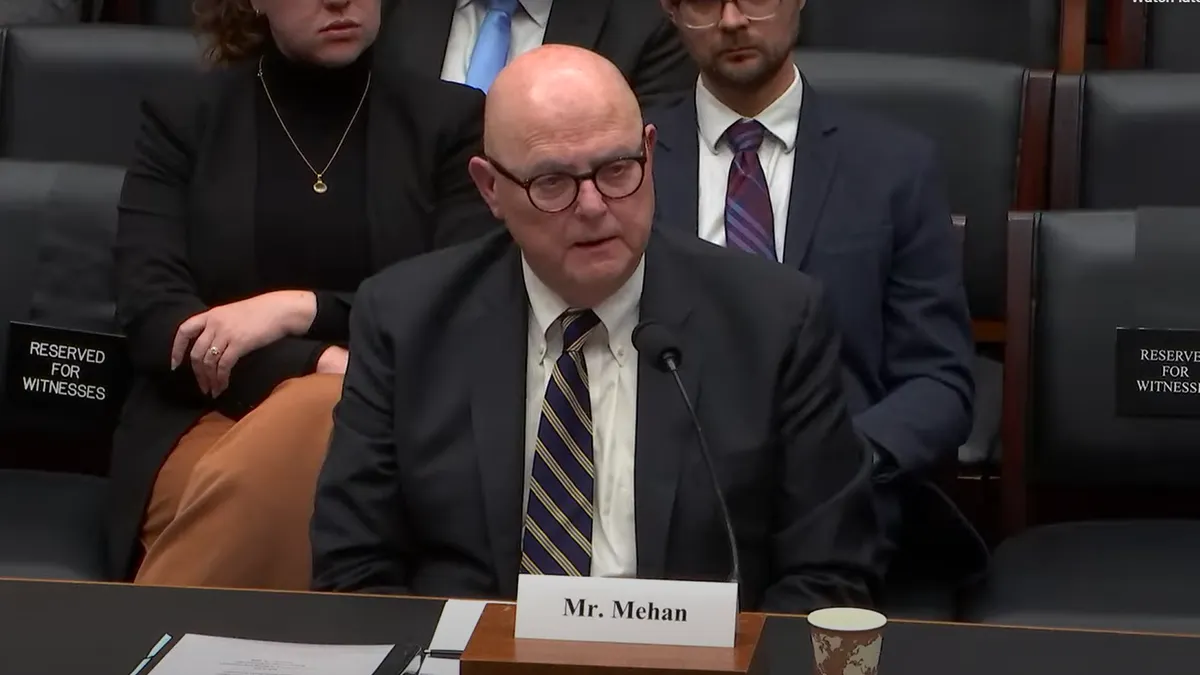

If water utilities must shoulder the burden of unfair PFAS contamination liabilities under CERCLA, ratepayer funding would be diverted from infrastructure and Safe Drinking Water Act compliance to instead pay for litigation or cleanup costs, said G. Tracy Mehan, American Water Works Association’s executive director of government affairs.

Water utilities that remove PFAS from water typically manage and dispose of these PFAS-containing residuals at a facility that accepts hazardous waste. If that disposal site ever becomes subject to Superfund cleanup, AWWA worries the water utilities would then be treated as a “potentially responsible party” under CERCLA.

“In effect, CERCLA punishes utilities for doing exactly what EPA requires them to do: treat for and dispose of PFAS,” Mehan said.

Emily Donovan, co-founder of grassroots group Clean Cape Fear, has worked on PFAS contamination issues for the last eight years due to high PFAS exposure levels in her hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina. Those high exposures have sickened many friends and family members, she testified Thursday.

Donovan said community activism has pressured her local water utility to more frequently test water for PFAS contamination and voluntarily upgrade facilities to address PFAS exposure concerns. The utility has also halted its land-application program of biosolids and now voluntarily sends such waste to a designated hazardous waste landfill.

While she sees those moves as small victories, an absence of higher-level regulations or guidelines makes it hard for water utilities to “act in the best interests of full disclosure to the public.”

“We believe lawmakers and federal regulators have not gone far enough in protecting our health and ensuring PFAS polluters pay,” she added. “We believe the entire class of PFAS should be designated as hazardous waste under Resource Conservation and Recovery Act,” a move she said would lead to better monitoring and make it easier for local governments to access certain polluter pay programs.

“A wastewater plant without accountability stops being a crucial point for monitoring and filtration and, instead, simply becomes a funnel,” she said.