While the waste and recycling industry recently reunited for its first in-person WasteExpo in two years, some attendees and presenters missed out due in part to ongoing pandemic challenges. WasteExpo Together Online, held virtually Sept. 13-14, offered another venue to discuss many of the sector’s most high-profile topics.

Catch up on some of our team's key insights about extended producer responsibility (EPR), environmental justice, waste-to-energy, technology, MRF contracts, organics recycling and more.

More states could implement packaging EPR, but policymaking is complicated

As more states consider establishing EPR for packaging, lawmakers and stakeholders will have to work together to create policies that set clear expectations and reflect market realities, WasteExpo speakers said.

Maine and Oregon became the first two states in the country to pass such laws this year. That momentum has inspired other state lawmakers to see EPR as a possible solution to stagnant recycling rates and a potential financing mechanism for municipal recycling infrastructure, said Resa Dimino, managing principal at consulting firm RRS.

Growing worldwide interest in creating circular economy systems, matched with consumer pressure urging brands to use more recycled content in their products, has also made EPR programs more attractive to some lawmakers. However, “not all EPR programs are created equally,” she said.

Dimino said it’s important that any legislation lays out clear responsibilities and requirements for the brands and retailers, with set performance standards. “It’s also important that state agencies provide good oversight,” she said.

Abbie Webb, sustainability director for Casella Waste Systems, said recyclers must come to the table and help shape the bills before they are passed. Recyclers can help lawmakers understand how market fluctuations and consumer confusion, as well as lack of infrastructure investments and other hurdles, could hamper MRFs and haulers from being able to implement EPR programs.

Webb also urged recyclers to participate in any resulting stakeholder and rulemaking processes. Casella operates in Maine, which anticipates beginning its process in July 2022. It could take until mid-2024 to sort out details like performance goals, producer payment schedules and other specifics, she said.

“This is where the rubber meets the road, where the details will be established as far as the framework for Maine's program, so it’s going to be important for us all to be engaged,” Webb said.

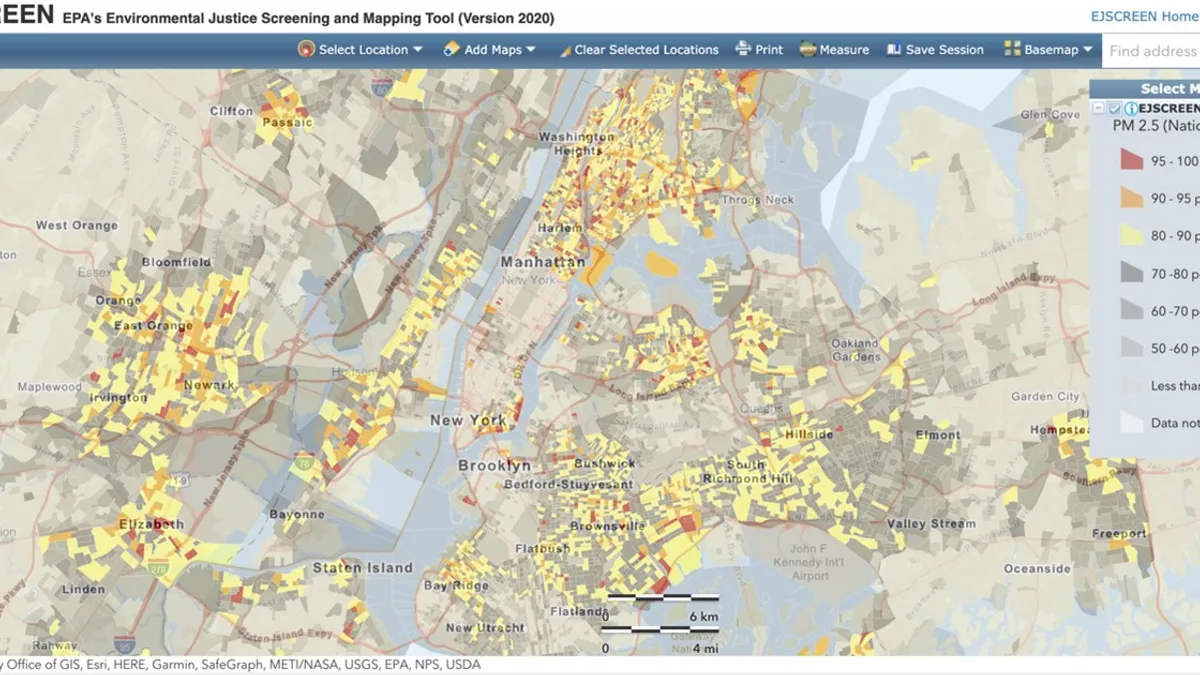

New Jersey’s environmental justice law could shape waste operations beyond the state

Environmental justice should be top of mind for operators working on waste operations, expansions and acquisitions, said Matt Karmel, an attorney with Riker Danzig. “The winds are moving towards further regulation in this space, and it's something that will impact the future of our industry for years to come.”

New Jersey passed a law in 2020 that requires certain facilities to consider the environmental justice impacts on nearby communities when applying for a permit to expand a facility, construct a new one or renew authorization to operate. The new law could go into effect by late next year, and Karmel urged operators of landfills, incinerators, transfer stations and other solid waste facilities to begin preparing.

Although at least ten states have some kind of environmental justice laws on the books, and numerous others have laws pending, “New Jersey’s law is regarded as one of the most groundbreaking because it has mandatory components,” he said. It requires applicants to provide an environmental justice impact statement that determines any new environmental or public health impacts the facility could pose to “overburdened communities.” It also requires facilities to hold a public hearing.

This process will slow down permitting, meaning those operating in the state need to plan ahead, Karmel said. If the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) determines a facility permit proposal would create a disproportionate impact that can’t be avoided through “additional controls,” new facility permits will be rejected. DEP can’t reject a permit for a renewal or an expansion, but can impose additional conditions to the permit.

The takeaway from New Jersey’s law is that waste facilities need to be more proactive in examining how their operations may affect communities around them, regardless of state policy. Companies that are considering acquisitions should also consider how the companies they might purchase approach these issues, since they can have revenue and operation implications.

“The regulatory landscape is changing really quickly. So you don't just want to look at it from a purely regulatory standpoint. You also want to do your due diligence,” he said.

WTE operators aren’t going anywhere, and they’re trying to shift the narrative

Following the expected close of Covanta’s sale to EQT Infrastructure, a Swedish group, both of North America’s major incinerator operators will be owned by private equity operators that see growing potential for the technology amid the climate change discussion. Like its counterpart, WIN Waste Innovations, Covanta sees a change in federal policy as one of the most necessary shifts to eventually spur the development of new facilities. In the meantime, the company plans to keep encouraging new discussions about waste-to-energy versus landfilling.

“I think a lot of the perception is really old and I think a lot of data points from pre-modern day waste-to-energy plants or incinerators keeps being dragged up to the forefront,” said Covanta’s Chief Operating Officer Derek Veenhof, comparing what he considers misconceptions about his company’s technology to questions around COVID-19 facts. “This is not a flat-Earth society. We’ve got to embrace science."

Covanta and other operators of similar U.S. facilities face ongoing pressure from community groups in multiple areas to curtail contracts or shut down sites over environmental concerns. Veenhof pointed to Covanta’s release of emissions data for specific facilities and early adoption of an environmental justice policy as signs of the company’s engagement.

Looking ahead, he said Covanta would be focused on capturing more value from its ash, finding new ways to show communities the potential local benefits of hosting facilities (such as steam for heating homes) and working to position the company as a climate change solution.

The latter point is a particularly contentious one among some environmental groups, but Veenhof said he considers the alternative path of landfilling residual waste increasingly unreliable. As an example, he said Hurricane Ida had disrupted transportation availability for long-distance waste exporting out of the Northeast and if the plan “as a society is just move it more rurally, to me that’s not the answer."

Then, now and next: Miami embraces trash tech, future of WTE

Just in the last five years, data collection in the waste industry has transformed from manual to automated. Technology has shifted numerous aspects of waste operations, including efficiency, environmental impact, and safety and accountability, described Michael Fernandez, Miami-Dade County’s director of solid waste management.

The industry’s tendency to collect data and track operations isn’t new, but it looks a lot different now. Documentation was done via Polaroids, and house counts were done with clickers, Fernandez recounted, after sharing a decades-old photo of himself with a roll-off truck stuck on South Beach.

Today, with a range of camera and artificial intelligence technologies available, “I think that data will help [prevent] safety issues, customer service issues. You can plan ahead now with this data,” he said.

Outside of the cab, Fernandez weighed in on fleet technologies such as compressed natural gas, electric and autonomous. On electric, he noted the apparent popularity of consumer EVs like Teslas on the streets. As far as electric’s place in refuse fleets, Fernandez pointed to New York City’s testing of Mack’s electric truck: “I think that’s gonna be the way of the future, and it’s going to help with emissions over the next 25 years.”

Broadly, Fernandez also predicts more waste-to-energy facilities will come online as landfill space runs out, and expects to evolve his agency’s own infrastructure. “We've been using this facility for close to 40 years. It is getting outdated, I perceive a new facility in the near future,” Fernandez said. An updated mass burn facility could potentially increase the volume of county waste being processed there to 70% to 75%. That energy could in turn power electric trucks, Fernandez suggested.

“The future is electric vehicles, and I think it's just a good connection [to have] the garbage trucks picking up the garbage, taking the waste, and the proceeds to power the trucks back up for the next day.”

Furthermore, Fernandez believes WTE facilities are going to have to be designed in more creative new ways and “get the buy-in from the community where it's kind of almost like an attraction point and not just your local dump,” he said.

MRF contracts have ongoing room for improvement

Keysha Burton, community program manager at The Recycling Partnership, emphasized her organization’s 11 essential elements for a strong MRF contract, which cover processing fees, revenue sharing, material value determination, material audits, rejected loads and residue disposal, and contingencies. Still, it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach, depending on community characteristics.

While TRP’s guide came out last year, the pandemic environment has raised new questions that may affect decisions. Burton said some MRFs have invested in equipment, technology and capacity expansion, while other communities have felt a budget deficit. In turn, the pandemic has impacted the evolving discussion around processing charges. “The one thing we want to remember is blended values were present before COVID so they will continue to be present after COVID,” Burton said.

In regard to whether municipalities ought to separate hauling contracts from processing contracts, Burton said it’s not necessarily a clear-cut answer. If possible, doing it all in one is ideal, she said, but that decision varies based on how much market competition is available.

“It’s really going to come down to: What’s available within your community? What is the landscape looking like in your community? What are the market constraints in your community?” said Burton, before “deciding whether or not bundling or unbundling makes the most sense for you.”

The anaerobic digestion boom has only just begun

Anaerobic digestion development was a highlight of WasteExpo this summer, with multiple operators touting big plans to expand in the years ahead. Following up on that discussion, Vanguard Renewables CEO John Hanselman previewed the latest details for his Massachusetts-based company this week.

In addition to multiple active New England sites, Hanselman said Vanguard is now in the permitting or construction phase for new facilities in Colorado, Georgia, Nevada, New York and Pennsylvania, with a goal to be in the top 25 metro areas within the next five years. The company’s Farm Powered Strategic Alliance, a group of companies such as Unliever that have pledged to scale up organics recycling, is also expected to grow with new names soon.

As Vanguard expands, Hanselman said the goal is to ensure regional “reliability and sustainability” by building multiple sites. He also noted depackaging and preprocessing capabilities are a priority for all projects moving forward, allowing Vanguard to handle any common packaging material except glass. While this isn’t a popular approach among some in the composting community, Hanselman said he viewed it as necessary until there is more standardization in accepted materials and collection methods around the U.S.

“Americans are used to zero-sort,” he said, referencing single-stream recycling programs. “It’s too hard, especially as we’re in the early days of the food waste recycling revolution. If we’re putting the burden on the recyclers to actually get their stream separated it really, I think, slows the implementation."