At the peak of its summer operations, Tom Gilbert's Black Dirt Farm had 2,000 chickens, a greenhouse full of tomato plants and a compost operation that could produce 850 cubic yards of finished material per year. His hauling operation collected food scraps from throughout Vermont's Northeast Kingdom region — up to 100 locations — and he felt Vermont was on the cusp of achieving something close to the circularity policymakers envisioned for organic waste when they passed the state's Universal Recycling Law in 2012.

But in 2018, a newcomer to the state threatened to upend the interconnected agricultural business Gilbert had developed. Agri-Cycle, an offshoot of a farm anaerobic digestion company based in Maine, contracted with grocer Hannaford to process its organics at locations in multiple states, including Vermont.

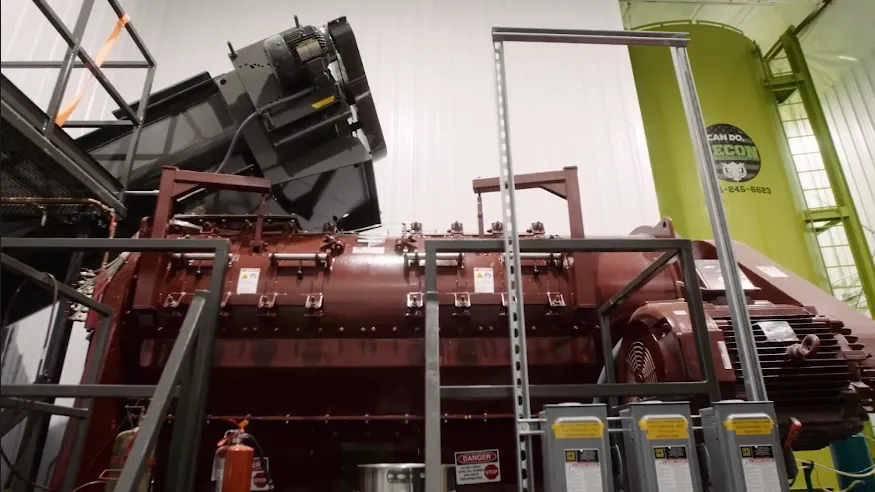

A few years prior, Agri-Cycle had built the first depackaging facility in Maine to supply additional material to a large anaerobic digestion facility. To feed the system — which smashes apart packaging and separates its organic contents at upwards of 20 tons of food waste an hour — the company began sourcing more and more organic waste.

Hannaford had been a client of Black Dirt Farm for multiple years, but the local composter was soon replaced by Agri-Cycle. In a matter of months, Gilbert said he lost his most important customers: the grocery stores that provide enough waste to make trips out to rural schools and businesses economical for a small hauler.

"It limited this really keystone aspect of our markets," Gilbert said.

When Agri-Cycle came to Vermont, the state's Agency of Natural Resources initially saw no reason to prevent the company from taking clean, source-separated organics to its out-of-state facility, so long as grocery stores weren’t sending their food scraps to disposal.

By January 2020, as the clamor over the arrival of a new technology in Vermont grew, the agency laid out its position in a public document: Depackagers could accept raw food waste and packaged organic goods together and send them through their machines as one stream. The technology, ANR reasoned, could capture more of the 38% of food residuals trapped in packaging and sent for disposal in Vermont. The agency cleared the way for large companies to absorb the streams of clean food waste that small composters in Maine relied on.

In the following years, issues like the Covid-19 pandemic and truck problems compounded Gilbert's troubles. But he said his business would be much better prepared to withstand those challenges if he hadn't lost about $100,000 in annual revenue due to the change.

"It's breaking me," Gilbert said. "We've worked really hard, and it's just incredibly disheartening to have these systems get further and further monopolized."

Officials have now acknowledged that they need to change direction. A 2022 law placed a moratorium on the construction of new depackaging facilities in Vermont and compelled the state to convene a depackaging stakeholder group to come up with policy recommendations. Since then, the volume of food waste sent to compost has remained relatively steady even as the total amount of diverted food waste in the state has grown.

This summer, ANR released its first draft of proposed language regulating depackaging facilities. In a shift, the proposal would require food waste generators and haulers to keep source-separated organics and packaged organics separate, potentially securing a clean stream for composters.

Vermont is one of two states to have a near-total ban on organic waste disposal — California is the other, and Massachusetts regulators are mulling a similar policy. But Vermont is the first to try and regulate a balance between depackaging and composting, wading into difficult questions around contamination, volumes and capture rate for organics in a rural state with high ambitions.

Natasha Duarte, director of the Composting Association of Vermont, said the state faced "unintended consequences" after depackagers began collecting Vermont’s organic waste. She said the new rules could be beneficial to composters, though it's unclear if they'd fully recover what they lost.

"If the state gets serious again about commitment to source separation and keeping as much of organic residuals going to local composters, ideally over time, there would be that rebound," she said. "But whether the final rules are going to be enough to support that, and how long it might take for that system shift to happen, is a question mark.”

The rise of depackaging

The market for organic waste solutions in the U.S. has grown considerably in recent years. With that growth has come investor capital and a push for consolidation.

Agri-Cycle was founded in 2013 to expand the food waste collection capabilities of Exeter Agri-Energy. The sister companies found Exeter's anaerobic digesters, which processed manure from Maine's second largest dairy farm, could use a higher proportion of food waste to maximize output.

Agri-Cycle spent up to $1 million to build its initial depackaging and collection network, according to a report from Mainebiz in early 2016. It then set about inking new food waste collection contracts.

Roughly a decade later, Agri-Cycle serves 850 commercial and industrial clients across 2,400 locations in 14 U.S. states. Agri-Cycle was acquired by the private equity arm of Closed Loop Partners in August for an undisclosed sum, and is now plotting further growth.

Agri-Cycle declined an interview request. In a statement shared with Waste Dive, a spokesperson said the company strongly believes that "once other options are exhausted––such as donations––organics recycling must be performed to the highest environmental standard through careful oversight of how packaged food waste is recovered and repurposed, and how foodservice packaging is managed and recovered in the process."

"Depackaging — when done responsibly — can play an important role in keeping food out of landfills and reducing methane emissions. However, we believe that all initiatives must be carried out in a way that maximizes recovery of valuable food scraps and valuable packaging materials, and does not overburden recovery efforts at the point of generation," a company spokesperson wrote in an email.

Agri-Cycle's takeover of Hannaford contracts rerouted a notable amount of organic waste. But a new depackaging facility built by Casella Waste Systems, a company whose annual revenues exceed $1 billion, caused composters further consternation.

The Williston, Vermont, facility opened in 2021, and is processing roughly 10,000 tons of waste annually. It mainly takes in food waste residuals from manufacturers and other large streams of packaged organics, spinning them in a machine that can rotate 400 times per minute. The resulting material is sent to anaerobic digestion.

Michael Casella, Vermont market area president, said the company keeps its source-separated organics and packaged organics separate. He also said depackagers can capture an important segment of the organic waste stream that composters may not want.

"You need a full-blown system to be able to really manage organics at scale," Casella said. "It's great to have little niche players, but it's sometimes difficult to keep up with the material, because it keeps flowing every day."

Anaerobic digestion companies have been eager to accept the slurry produced by depackaging facilities. Casella has offtake agreements with Purpose Energy, which has built four digesters in Vermont in recent years. Purpose's latest plant features a pipeline directly to a Ben & Jerry's manufacturing facility, feeding the digester a steady diet of off-spec ice cream in addition to other organic waste.

The state's Universal Organics Recycling law set a series of deadlines after which a growing number of facilities needed to divert their organic waste, leading to the residential organics diversion mandate on July 1, 2020. Since that final stage, digesters have been a major beneficiary of growing organics tonnages, according to ANR data shared with Waste Dive.

As large companies capable of building depackaging facilities have descended upon the state, composters have been left to stew over limited tonnages and fears that their old anchor clients have grown complacent over contamination of the organic waste stream.

“It's like a Pandora's Box,” said Gilbert. “Suddenly, these grocery stores get used to not having to separate the packaging, and it's very hard to get them back.”

Crafting policy

In the years leading up to and immediately following the 2020 ban, facilities of all kinds capable of processing organics seemed to be preparing to take in the added capacity. The number of haulers collecting food scraps grew from 12 to 38, according to the state’s most recent materials management plan. And companies approached ANR attempting to permit depackagers, a technology that was niche and relatively unknown to Vermont agency staff at the time, said Ben Gauthier, an environmental analyst in the agency's solid waste management program.

During that time, regulators were focused on maximizing diversion. But "depack opened a weird door that we didn't really have an answer to," Gauthier said.

The agency’s 2020 guidance document ultimately provided flexibility for food waste generators to send their organic waste wherever was most economical. It allowed the commingling of organic waste, clearing the way for businesses like grocery stores to halt the more labor-intensive process of separating uncontaminated produce from the packaged meat, canned goods and other materials that might not have been recycled otherwise.

Suddenly, a regional manager of a supermarket chain could contract with a large hauler like Casella for all of its waste across multiple locations and avoid the specialized, uncontaminated stream that small local composters needed for their business.

"On one hand, it makes it harder for the small composters. But on the other hand, it makes it easier for the supermarket managers," Gauthier said. "They don't have to be dealing with a pig farmer in northern Vermont and a small composter in southern Vermont."

The policy was immediately unpopular with composters. Duarte said many lost key contracts, and several facilities either delayed or cancelled expansion plans.

The legislature responded with Act 170, which created both the moratorium and the stakeholder group. The group included Gilbert, with Black Dirt Farms; Michael Casella; and representatives from Ben & Jerry's, digester company Vanguard Renewables, the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets, Green Mountain Compost and the Vermont Retail & Grocers Association trade group.

In their final report, a majority of the stakeholder group backed language prohibiting the commingling of source-separated and packaged organics. The representatives from Casella, Vanguard Renewables and the grocers’ trade group opposed it. The representative from Vanguard noted that “source separation does not guarantee that the organics stream is free of contaminants” in his recommendation, pushing back on one of composters’ concerns.

ANR chose to adopt the prohibition in its draft solid waste rule revisions, which it released in July. The agency is also proposing to prohibit feeding source-separated food residuals into a depackager, which would ensure the machines don't absorb the kinds of materials that could be sent straight to composters.

It’s also taking steps to limit contamination. ANR has already begun inserting load audit language into organics processing facilities’ permits to ensure waste generators and haulers receive feedback on impure material, Gauthier said. And the agency is proposing to require depackagers to remove outer plastic wrap or packaging from incoming bulk loads, reducing the amount of inorganic materials sent through their machines.

Stakeholders want to see other policy tweaks as well. The Composting Association of Vermont, for instance, is still pushing for ANR to remove language allowing exemptions to the commingling prohibition in cases that are “preapproved by the Secretary.” The group argues that such language is too vague and risks undermining the rule.

Casella is also seeking clarification on whether the state will allow the commingling of food waste if haulers take the material outside of Vermont. That could allow out-of-state haulers using practices not allowed under ANR's rules to siphon off valuable organics streams, the company argues.

Rather than issue less legally binding guidance like it did in 2020, the agency is planning to go through the more permanent process of making revisions to its solid waste rules, which involves an additional public comment period next year. Gauthier estimates the changes to Vermont's depackaging rules would likely go into effect next summer, with a “soft rollout” of any of the prohibitions to give companies time to comply.

He said the agency has been chastised by the legislature and composters for its current depackaging policy. And he said composters have a valid gripe over the time it’s taken to craft new, more supportive policy.

But Gauthier contends that’s inherent to the nature of good policymaking. And he hopes that by taking a more deliberate approach this time around, the state can set up its organics recycling ecosystem for long-term success.

“I don't think departments generally like to be doing that, saying, ‘Hey, we have egg on our face here,’” Gauthier said. “Moving this stuff along and reversing a course like that is something that does take time.”