Right-to-repair bills are again popping up in numerous states this year. Advocates expect fresh momentum on consumer electronics bills along with bills related to agricultural, automotive and wheelchair repairs.

In the first few weeks of January, more than 33 right-to-repair bills have been introduced in 13 states, according to advocacy group The Repair Association.

These bills tend to differ from state to state, but most call for original equipment manufacturers to make parts and repair instructions available to the general public.

The recycling industry has typically viewed such legislation as a tactic for diverting e-scrap from disposal and bringing in new business for e-scrap recyclers and refurbishers. Diverting the material may also help reduce fires caused by lithium-ion batteries in the waste stream, long considered a major safety concern for the industry.

Advocates have also framed the laws as an important way for consumers to extend the life of their devices, particularly as concerns about the economy deepen.

In the past, companies like Apple, the Federal Trade Commission and some state attorneys general have also voiced support for such bills.

Yet some electronics trade groups have said right-to-repair laws could create digital security issues as well as safety concerns for people who don’t know how to properly repair their equipment.

“There’s a lot to point to” that shows 2026 will be another busy year for legislation, said Nathan Proctor, who leads PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign. Much of the bill activity is still going on in the background, but PIRG and other groups expect more details to emerge in coming weeks as more state legislatures return to work.

This year, repair advocates expect more bills to include provisions that ban parts pairing, a practice that ensures electronics can only operate with manufacturer-approved parts or software. That has become a more common feature in newly passed right-to-repair laws.

The Repair Association says it expects more bills to explicitly include software updates that address manufacturing defects and security vulnerabilities. States with existing laws are also expected to introduce laws that expand that coverage or address loopholes.

Some hope the momentum from previous year’s successes will also give 2026 bills a boost. As of Jan. 1, Colorado and Washington’s consumer electronics laws are now in effect, as well as Nevada and Oregon’s laws for wheelchairs.

In July, Connecticut will enact right-to-repair elements of a consumer protection omnibus bill that passed last year. Texas will enact its right-to-repair for consumer electronics law in September.

Meanwhile, several bills introduced in 2025 will carry over into 2026 in states with a two-year legislative calendar: Pennsylvania, Ohio, Massachusetts and Wisconsin are among them.

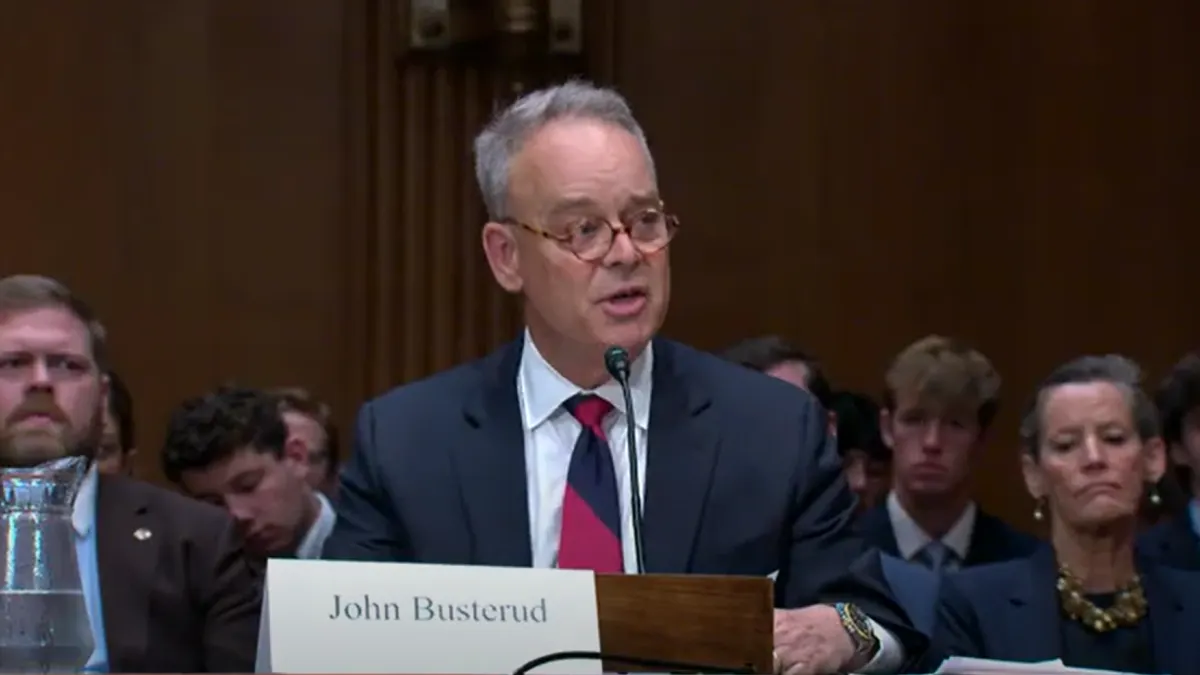

As in previous years, more momentum is expected to come from state-level legislation, though several federal bills are still in play that aim to address right-to-repair on a national level. During a U.S. House Energy and Commerce subcommittee hearing last week, groups representing independent auto repair shops advocated for a nationwide right-to-repair framework like the one proposed in the federal Repair Act, which calls for wider access to repair and diagnostic data needed for auto repairs.

Meanwhile, federal lawmakers in October introduced the Farm Act, which would make similar parts, software and tools available for farmers to fix their agricultural equipment in a move lawmakers say supports “farmers’ agency.”

Right-to-repair bills could encounter pushback from well-known opponents, including some in the auto industry.

The status of Maine’s LD 1228, regarding recommendations from a state right-to-repair working group, is up in the air this week. Gov. Janet Mills vetoed the bill, saying last-minute additions to the bill would have allowed automobile manufacturers to decide how vehicle telemetric data would be accessible to independent automotive repair shops. That provision was not part of the working group’s original recommendations and gave too much power to the auto industry, she said.

The House last week voted to reverse the veto, and the state Senate is expected to take up the matter this week. Mills said the Maine legislature should instead focus on another pending bill, LD 292, which she said would enact the working group's recommendations without the provision that she disagrees with.

Momentum for bills in other states has been slow. Massachusetts’ consumer electronics bill, S 189, mirrors similar bills that have been introduced in that state since at least 2017.

Here are some highlights from the growing right-to-repair bill list. Which bills or states are you tracking? Email us at waste.dive.editors@industrydive.com.

- Delaware: HB 176 includes agricultural equipment.

- Florida: H 1255 covers portable wireless devices and some agricultural equipment. (S 806 is its companion bill.)

- Florida: SB 586 covers mobility devices.

- Maine: LD 292 calls for carrying out recommendations from the state’s Automotive Right to Repair Working group.

- Massachusetts: S 189 includes consumer electronics.

- Massachusetts: H 452 includes some agricultural equipment.

- Massachusetts: H 398 adjusts language related to the right-to-repair for electronics law, specifically a required notice to consumers related to telematics repair rights.

- Missouri: HB 2871 covers consumer electronics.

- Missouri: HB 2257 also regards consumer electronic repair.

- New Jersey: S 2085 includes certain consumer electronics.

- Ohio: SB 176 covers most consumer electronics over $10.

- Pennsylvania: HB 1512 covers consumer electronics.

- Wisconsin: SB 148 covers certain agricultural equipment.

- Wyoming: HB 15 covers most consumer electronics.